Hiking the Exit Glacier and the Harding Ice Field

A single sheet of ice all the way to the horizon. This was the Harding Ice Field, a massive frozen wilderness that leads to multiple glaciers in the Kenai Fjords area. My sister and I stood there on the viewing promontory, staring out into the vast white area before us. If you’ve seen Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, we were on Hoth. A cold wind blew in our faces from the ice field, a fine mist of ice crystals assaulted us on that rocky outcrop.

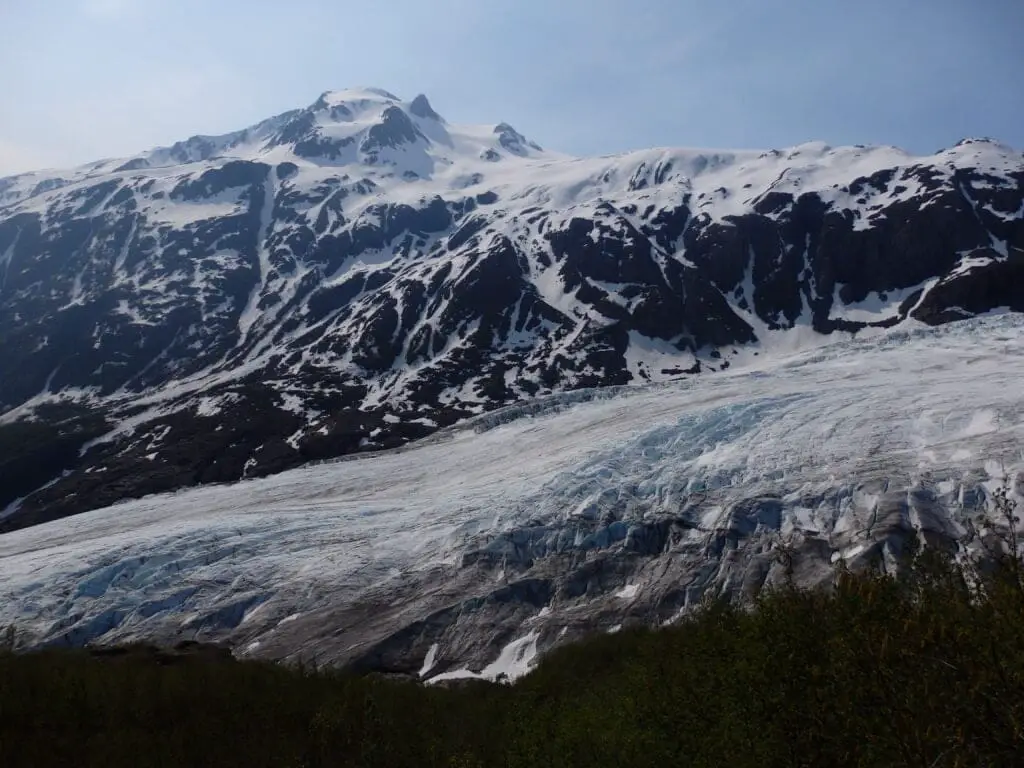

Exit Glacier

From every direction, snow surrounded us. There was snow, there was sky, and there was nothing else. Just below us, the Exit Glacier wound its way through the valley down towards Seward, Alaska. It was May, and in this place May is late winter. The rocks we stood on were the only solid ground we had felt in over two miles. The Park Service classifies this as a strenuous hike, and this was true, especially given how hard we had to fight the snow in May.

Later in the season, once the trail is clear of snow, I suspect that this hike would be fairly mild, as the elevation gain is only about one thousand vertical feet per mile. But we were not here late in the season, and we cursed the snow as we made our way up from the valley.

Harding Ice Field

About three hours earlier, we had set out from the trailhead at the parking lot. Where we began, it was a wonderful, warm day. And then the trail began to climb, up and up through the forest, then dense brush, and then over a ridge. And on that ridge, the weather changed from seventy degrees to somewhere in the thirties and the trail vanished beneath hip deep snow. As it was late in the season, this snow was, ah, fickle. For a few hundred yards it would be perfect snow, firm enough to stand on but loose enough that we did not slip on it. And then, suddenly, one of us would break through and go into the snow up to our hip. And that process repeated for the second half of the four-mile trail to the Harding Ice Field viewing point.

At a point, we simply stumbled our way up the trail, as we were so tired from post-holing through the snow. After losing the trail beneath a layer of snow, we had been following little pink surveyor’s flags, placed there by a park ranger to mark the trail. And then, up ahead of us, we saw a person, the first one we had seen all morning. It was the park ranger, and once we passed him, there were no more navigational flags.

We made it up to the viewing point before the Park Service did.

When we saw a few small shelters and signs, we knew we had reached the end of the trail. This was the observation point for the Ice Field. The view from this area was… other-worldly. The way the pure ice and snow stretched out before us. Three hundred square miles of ice. That’s about a quarter of the size of Rhode Island, and we stood there in awe of this. Formations like this once covered much of North America. And when they receded, they carved out valleys and moraines and lakes. They formed the Canadian Shield and gave shape to what we call the Rockies and Appalachians.

Ancient Glaciers

And in this place, one of the last pieces of that pre-historic history remains today, shrinking faster than ever, but still impressive. Thousands of years ago, this would have been commonplace, but looking at it now was surreal. The Harding Ice Field, is like a fossil, an ancient piece of the past entombed by time itself, preserved from change. And though this ice field is but a tiny remnant of a time that passed long before humans settled into cities, this vast sheet of ice is a monument to the forces that shaped our world.

The Power of Nature

Have you ever wondered why some valleys are shaped like a V and others are shaped like a U? U-shaped valleys once contained glaciers like those before us, and over the centuries, the tremendous weight of the ice pressed down the rock itself until the valley flattened out. A V-shaped valley was simply carved by water, formed by the erosion of a river, not the immense crushing power of a glacier.

After some time we began to grow cold, especially as the wind picked up and blasted us with glacial snow and ice pellets. And so we began our descent, much easier than our ascent. We actually slid down quite a bit of the firmer snow to save time and effort. We were low on water too, oops. And then, almost in an instant, we crossed back over that ridgeline and left the winter behind. Now, instead of impenetrable ice and snow, we saw the green valley ahead of us, trees and brush and no snow at all.

From there, we almost flew back to the trailhead. This had indeed been a difficult hike, made worse by the snow conditions. The Harding Ice Field is a fairly popular tourist destination, though those people typically come in July or August when the cruise ships make the rounds of the Alaskan coast. I would love to go back, maybe even in winter for a snowshoe hike.

Summary

Witnessing the grandeur of snow and ice, a glacial formation predating the human concept of time, was breathtaking. An ice field of this nature is akin to a fossil, preserved in one location for thousands of years. By observing it, we were glimpsing history, a snapshot of what this continent once was. This realization made the challenging hike entirely worthwhile.

We appreciate reader feedback. Which glaciers or ice fields have you visited? Have you had the chance to see Exit Glacier? Share your experiences and thoughts in the comments below!

Excellent article! We’ve been to Exit Glacier and the descriptions are perfect.

Well written article on one of Alaska’s best attractions. Most people just do a bush plane fly over, nice that you hiked and photographed it.

I lived near Exit Glacier for a few years and hiked around the base area, but in Cordova me and some pals hiked the Sherman Glacier. Very dangerous, but we were young and fearless.

Great article.